#16 :: Where ideas are born

Or, why better futures rest on unimpinged imagination

Squelch confidently into the unknown

I never thought I’d be trusted, aged 15, to measure up oak struts for an actress’s apartment refurb.

Architectural practice, let alone the world of work, was unknown terrain back then. Spending a week’s work experience in an architect’s office started me thinking about how my teenage interests (computers, French, painting, design) might possibly converge.

In the UK, work experience for 15 year olds used to be mandatory, but cuts mean that’s no longer the case. Last week, the charity Speakers for Schools reported this is blocking state school pupils' access to top university courses.

I was lucky that work experience was possible at my school. But the options were wholly uninspiring.

At the beginning of term, a list of opportunities circulated: A stint in the local care home; at an HMRC tax centre; or the town centre supermarket.

I had other ideas.

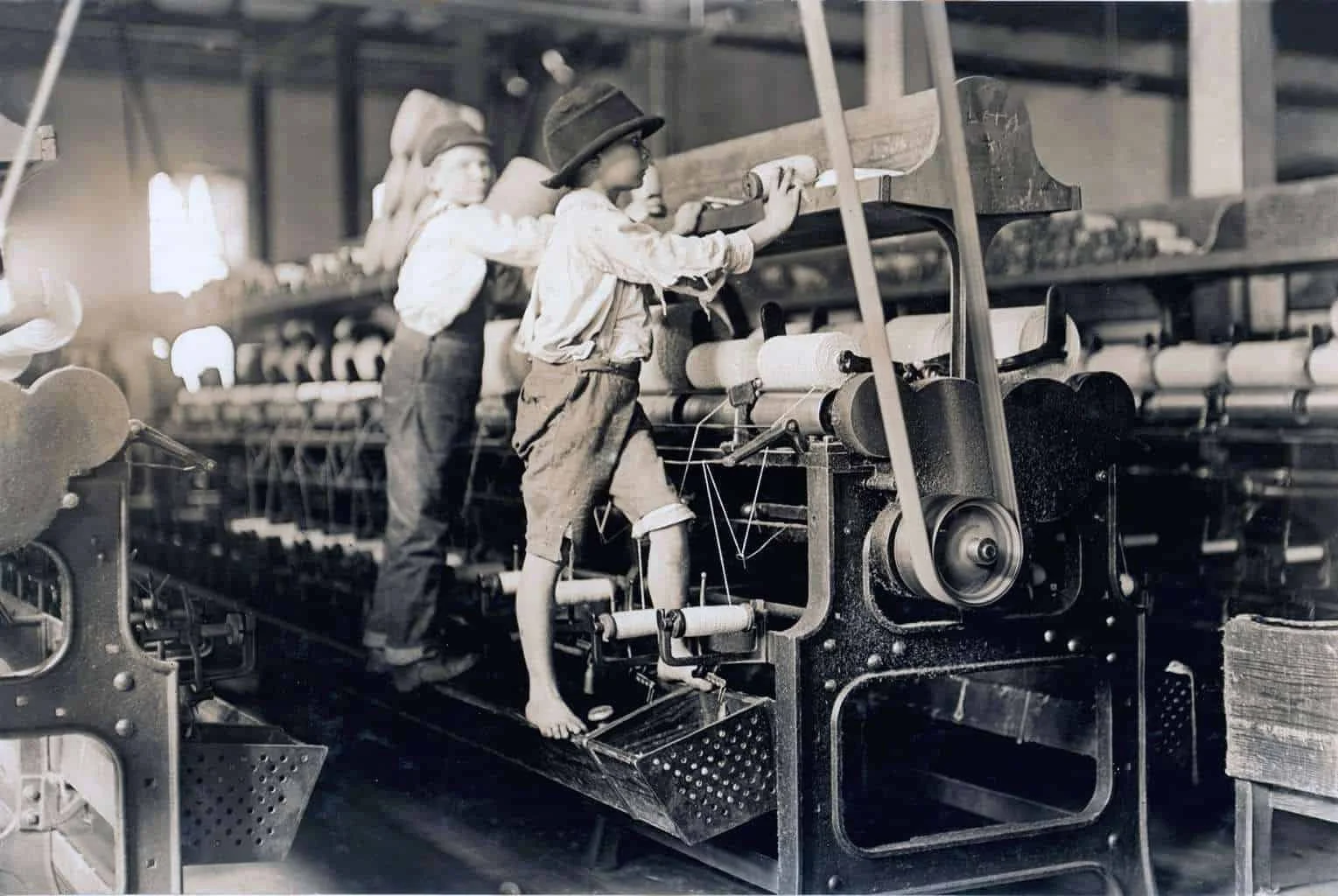

Not this sort of experience. Cotton mill, 1830sHellbent on exploring computers, design and painting, I set about identifying, contacting, then bothering every architectural practice in the area. One agreed: thank you Condie Plummer.

It was a week of firsts: Measuring up at the glamorous apartment; squelching in borrowed wellies on a wet building site; drawing blueprints; trying Mexican food.

Remembering Condie Plummer this week made me think about trajectories: How things are brought to life; where ideas are born.

Besides securing a place at university, work experience is important for all sorts of reasons: Confidence, experimentation, exploration, imagination.

Ultimately, it’s about generating better futures. For individuals, communities, countries, the world.

It’s so critical, because it gives young people space to dream, imagine, aspire. But that has to be in the right context.

Or this sort. Manuel, a shrimp picker, 1912Why is this important?

An early taste of a different reality sets the stage for developing vision. And creating a vision rests on unleashing the imagination. Daring, however brazenly, to conjecture how things could be.

Aspiration is deeply entwined in this process. But its early quashing decisively extinguishes vision. Kids give up dreaming about what could be better.

At scale, it’s exactly this thinking that makes for a dulled society full of malaise, a stagnated economy, creeping mediocrity. There’s no advancement without imagination.

Yet unveil the horizon, and new potentials come into sharp focus.

So work experience in the right context is critical.

Future breaks

It’s the ultimate dispiriting catch 22: “No experience, no job”.

Giving young people a life-altering first break not only generates better futures. It’s also plain good business sense. Here I’ve gathered a list of bodies providing platforms for recruiting emerging talent into your firm:

Speakers for Schools - A UK-based charity connecting state schools pupils with work experience opportunities

Zero Gravity - A platform matching university students from low-opportunity backgrounds to mentors, scholarships and internships with major firms

Movement to Work - This UK charity supports employers in giving underprivileged young people a foot-in with structured experience programs and apprenticeships

Framing a de-fog experiment

Architecture, I decided, wasn’t for me. But it turns out Condie Plummer was a quasi design sprint, confirming the creative industries as the right pathway.

When creating any new idea, a phase of experimentation allows clearer thought. Try, fail, learn … do something differently.

As a design research studio, I de-fog others’ problems on a daily basis.

I’ve found that providing people with space to try unravels all sorts of helpful things: Confidence around future uncertainty; reflection about what’s right and what’s not; hope for possibilities yet to be created.

When seeking change of almost any type - from designing one’s life, to imagining a self-driving passenger vehicle - research experiments de-fog issues, bringing clarity.

So, how to move towards a vision as yet unknown? Here are my tips for creating from scratch:

Create a framework: Structuring an exploration sounds like an oxymoron. But frameworks (e.g. a set program with defined activities) enable productive experimentation that move forwards by uncovering new insights

Ask specific questions: Thinking in abstract, general terms about “the future” is difficult. But in the confines of a helpful question (e.g. “is architecture the career for me?”) learning can take place. Guardrails allow for working backwards

Creative flexibility: A relaxed and open mind is essential, but can’t be switched on and off. It requires the right context. That may be a warm-up routine, a ritual, a special book or place. It must permit the connection of insights and ideas. (In fact, the most valuable innovations always come from the fringes of what’s initially imagined)

Writing by hand is thinking on paper

Last week, I acquired my first Drehgriffel. Drehgriffel is a 13cm pocket pen, produced by German stationers Leuchtturm 1917. Its name is derived from the German ‘dreh’ meaning to twist, and the Greek ‘grapheĩon’ - the world’s first writing instrument.

Drehgriffel in mint green, by Leuchtturm 1917Opening the understated, perfectly designed triangular box, I had a tingle of excitement — this is a special product.

Turns out Drehgriffel is the epitome of good design: Beautiful, simple, sustainable.

“The hand is the window to the mind”

— Immanuel Kant

Like Kant suggests, I’ve been seeking out reasons to scribble because of my Drehgriffel. It’s joyfully unlocking new insight.