#3 :: The future of education

Or, how veering off rails augments tech learning

I’ve learned a lot about, well, learning, first through lecturing, then working in academic research, and later building edtech product projects. Right now, there’s a confluence of conditions forcing flux in education. For a set of systems conceived hundreds of years ago, this is no bad thing.

Tuition fees are sky-rocketing, and students are having to get creative about how to pay for education; the pandemic has forced at-home learning; universities are cutting arts and humanities courses; and degree holders are no longer commanding higher earning power, finding themselves in lifelong debt.

But what that means is more avenues for alternative learning off the rails of a campus. And tech is at the forefront of reshaping learning. Digital platforms and content. New methods to learn. Apprenticeships and vocational courses more visible, viable and attractive than ever before. This week, we look at the design of learning and the learning of tech. The future of education.

Collected this week:

Lessons from Estonia

Democratising learning

The future is personalised

01: Lessons from Estonia

Estonia has the best education system in Europe, according to the OECD. Its schoolkids perform amongst the top globally for reading, maths and science. And they are also some of the happiest. Technology has driven this success. The Estonian government has invested in high speed connectivity for schools, and devices for all pupils. Robotics and coding are taught from the age of seven - the year when school starts. And most stay until 19.

The attention and investment in education is being reflected in the strength of companies emerging from Estonia. It has become a tech haven nurturing entrepreneurs, founders and their startups: Skype (communications), Bolt (transport), Wise (fintech), Playtech (gaming). Gargantuan for a tiny country of 1.3 million.

Tech and entrepreneurship are designed into the fabric of society. It’s a mindset that allows people to get things done. All government services are facilitated and managed online. Teachers have autonomy to build and create lessons and learning methods. And rather than rote learning, skills like problem solving, application of ideas, complex communication, critical thinking and pattern recognition are fostered and developed. National prosperity and progression have been natural by-products.

Above: Viktor Siilats, Krista Siilats, Keith Siilats - Stroika (1988). Computer animation. From Early Estonian computer art exhibitionThis is interesting because:

A startup scene is emerging around the biggest cities Tallinn and Tartu. Skills and talent are plentiful, alongside a discourse centring on innovation and entrepreneurship. This is attracting innovators from elsewhere. Echoes here of the start-up scene that emerged in northern California in the late 1970s, and the loose interdisciplinary collectives that have driven Lombardy as the global hub for innovative design since the 1980s.

Estonia’s entire system is designed to facilitate learning. Alongside equality, openness and entrepreneurship, knowledge and education are part of the country’s values. Kids are automatically bought in. Things like free lunches, trips, books, transport make school non negotiable. For Estonians, education is an investment in the future.

Especially unique is the lack of subject compartmentalisation. This leaves lots of room for cross pollination of ideas. VR in the classroom for history, chemistry, languages. Collaboration and skills focus. This is essential for futureproofing, and allows pupils to synthesise, implement and apply their own ideas.

Above: Renee Kelomees, Geom I (1994) Amiga Deluxe Paint. Early Estonian Computer Art02: Democratising learning

There’s a skills crisis in tech. Schools and universities are struggling to produce the quality and quantity of grads required for the jobs of today, let alone tomorrow. Enter the mavericks. Private, philanthropically funded institutions are being created and innovated to break moulds and bridge the chasm. AI, coding, programming, digital systems, interface design are the order of the day. 42 (France and global), 01 Founders (UK), Dyson Institute (UK) are democratising learning.

Democratisation means flipping around the systems of the past. 42 talks about “learning how to learn”. The philosophy goes that tech is changing so rapidly that learning programming languages is useless. So, like in the schools of Estonia, it’s about frameworks and tools, problem identification and problem solving, complex communication and pattern recognition. The ability to adapt to change, and apply a toolkit to any problem.

Collaboration is another pillar. Coming together to crack problems. That’s important for building motivation, engagement, and being inspired to push beyond what you can do alone. Here, failing is winning - a crucial part of learning, creating and improving. Learning with peers allows creative hacking and implementation, an ocean away from lectures and tutorials, with their focus on knowledge and understanding. So exams are out, and projects of increasing complexity are in.

And lastly, there is opportunity and access for lots of different backgrounds, mindsets, abilities, geographies. For example, 37% of 01 Founders is female - that’s more than 3 times more than conventional computer science degrees - with the aim for 50/50. This makes sense. A broad range of backgrounds brings diversity of thought, ideas and execution. And this is crucial for building the products that society is going to need: a metaverse is only going to truly find purpose if it’s populated by a range of meaningful experiences.

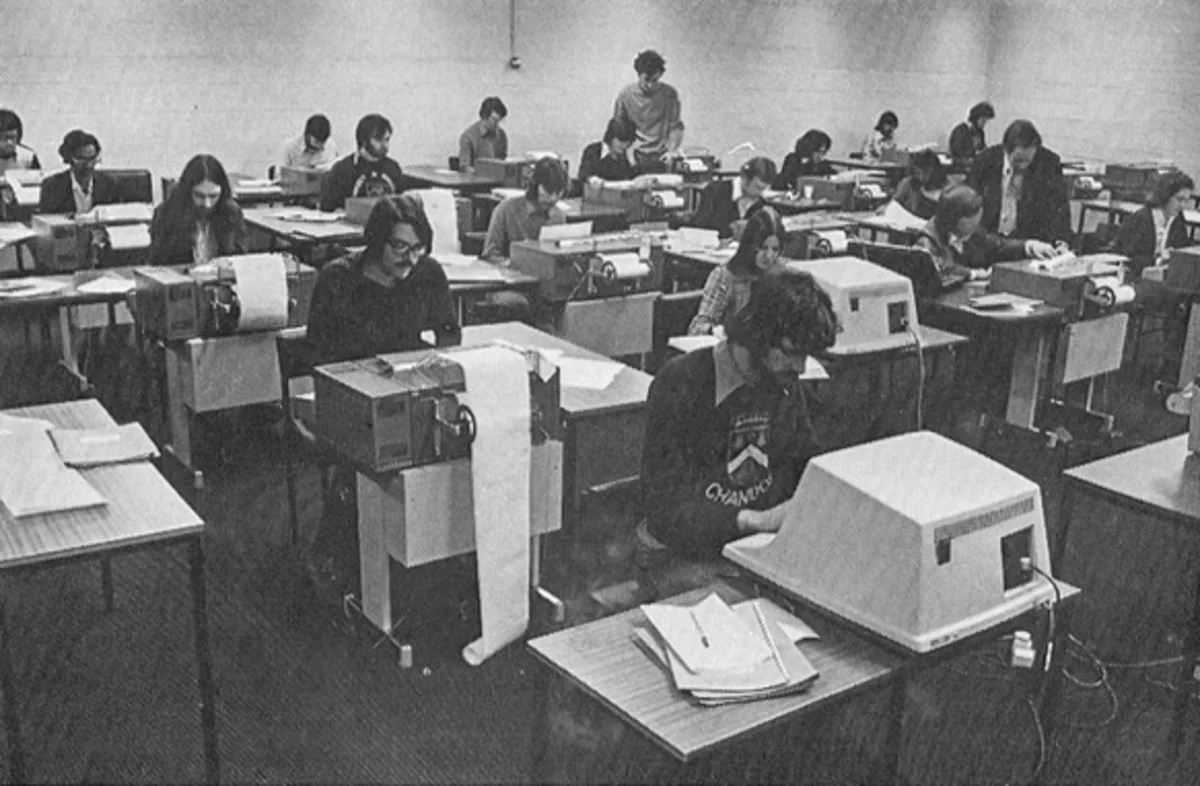

Above: University of Manchester, Department of Computer Science, early 1980s

This is interesting because:

These programs are social models. They’re about bringing opportunities to people and societies and economies. Developing talent and business and prosperity nationally. Wins all round.

By making tuition free, the model departs from education as business. By innovating from the core, the weaknesses of traditional education - spiralling debt, outdated material, siloed learning - are being circumnavigated.

At 01 Founders, successful grads are automatically offered a job with one of the institute’s sponsors. Another win-win - these companies get to build their talent pipeline with the right kind of skills.

03: The future is personalised

The great models of disruption of the last decade - Amazon on shopping, Netflix on TV, Spotify on music - have shown that people respond best to being able to personalise how they shop/watch/listen. The same is now happening for learning. Sal Khan, an MIT maths graduate and hedge fund manager, was asked for help by his cousin who was struggling with high school maths in the early noughties. What started as telephone tutorials once per week became remote lessons for groups of cousins, practice exercises, and finally Youtube tutorial videos. These were being watched by tens of thousands online, before being picked up by Bill Gates.

The Khan Academy launched in 2008, and funded by Gates, Elon Musk, and Eric Schmidt, brings free, high quality lessons to a global audience. Democratisation of learning in its highest form.

Aside from the need during the pandemic, Khan has recognised two key things. First, that digital natives are creative, with high expectations, and a requirement for active learning. They are resourceful, capable of proactively seeking supplementary material that reinforces their classroom learning. The Khan Academy’s beauty is that it enhances traditional schooling. It’s also been a lifeline for remote and underprivileged kids globally, and has amassed 135m subscribers worldwide.

Second, Khan recognised the need for personalisation. There are lots of ways to learn, and nuanced learning styles. For instance, when it comes to coding and building, there’s a marked difference between the approaches and preferences of left brain/right brain dominants. Being forced into the wrong box - such as forcing creative thinkers to read lots of detail - makes things hard, uncomfortable, even impossible. The Khan Academy taps into the need to find the right kind of materials. There are now more than 8,000 videos online.

Above: Children proudly using their new BBC Model B in a school near Morpeth, UK, 1983This is interesting because:

Khan’s concept is hybrid. The pandemic highlighted that traditional structures can’t, and shouldn’t, be shifted directly into digital. Products that have attempted to simply recreate the classroom or lecture theatre have failed. Remote learning doesn’t work like this. But different modes can be mashed together.

The “soft” skills we learn at school – play, teamwork, communication – can only be learned through interfacing with peers. This can be enhanced by tech, but VR and programs can never replace real-life settings. Rather, Khan’s approach is about augmenting real-life.

Khan is on a mission to improve learning - peer to peer learning, like at the 01 Founders, is the next step in this mission. His Schoolhouse.world platform allows pupils to become accredited to teach courses to other pupils globally.